Writing Back to Thomas James

I have long believed in a sort of divine intervention when it comes to the books that have impacted me the most. I still remember the moment I discovered The Outsiders (1967) by S.E. Hinton on my sixth-grade teacher’s bookshelf: an excited rush as I held the bright orange cover in my hands and read the distinct first line, how that book enunciated all of my middle-school angst and spoke for me in a way a book had never had before. With Thomas James, I was less convinced at first.

When my junior year high school AP literature teacher placed a copy of Letters to a Stranger on my desk during class and told me that I should really read the poems we didn’t cover in class, I didn’t know I’d fall into the tradition of stealing that surrounds James’ work (read on for details…). I wasn’t entirely sure how serious my teacher was, but I knew that I would be slipping it into my backpack along with loose papers and decaying granola bars to hold it hostage over the weekend.

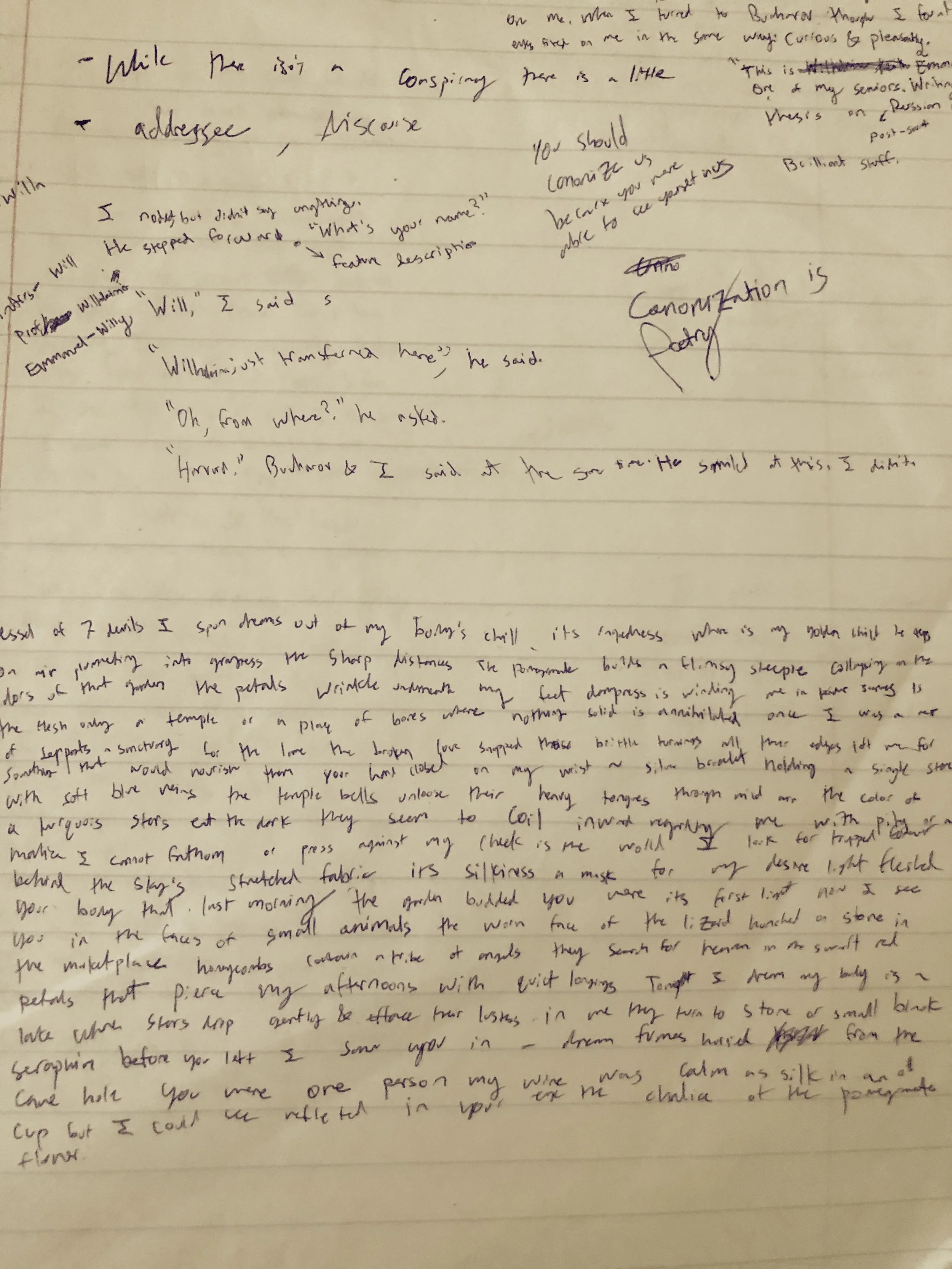

Truthfully, I had zoned out when we covered his poems “Laceration” and “Dragging the Lake” in class. However, out of all the poets we studied (Shelley, Whitman, and Wordsworth), James had seemed the realest to me. I found his style unsettling. James’ world turns the everyday into death and decay. His sense of rhythm is prickly and abrasive — it sits in your gut and sloshes around with unsteadiness. The line that always sticks in my head like the refrain of a catchy song comes from “Magdalene in the Garden”: “Now I see you in the faces of small animals-- /the worn face of the lizard hunched on stone.” There is something senseless about his word choice, feverish and sweeping. While I find myself unable to fully piece together what he is saying on a basic comprehensive level, something about it makes perfect sense. It’s the suggestion of melancholy through hallucinations grounded in reality and in the body.

Lucie Brock-Broido writes in her introduction to the long-overdue anthology of Thomas James’ poems in 2008 that “Letters to a Stranger is the only book [she’d] ever stolen.” In her introduction, she explains that because of the murky state of publication rights following James’ suicide in 1974, much of his poetry remained unpublished and secretly distributed amongst a select group of poetry lovers for years. Brock-Broido describes that “when [she teaches] this book, invariably, young poets seem to want to go home (as soon as possible) to write back to Thomas James.” If you look closely at the silence and isolation James wrote about frequently, the silence that surrounds his poems within critical circles seems somehow larger, more twisted, and more tragic.

Like Brock-Broido, I initially stole Letters to a Stranger (from my English teacher). That afternoon, I squirreled myself away in the corner of the changing room at my ballet studio and read it before pointe class. As I began to fully read it, and get used to his rhythm, I found I could not put it down. I can’t say I fully understand what I see in Thomas James’ work, but I know I feel it deeply. Even after my rebellion faded and I finally returned the book to my teacher that Monday, I couldn’t get the words out of my head. Now I see you in the faces of small animals.

Eventually I bought my own copy because I could not fight back the urge to read it constantly. I have now read and re-read Letters to a Stranger a handful of times and can recite “Magdalene in the Garden” and “Letter to a Mute” by memory. I seldom travel without it carefully tucked in my bag. It is the only book I consistently carry between home and college during vacations. Worshipping the physical book feels frivolous and unimportant, but I can’t seem to stop myself from doing it. James is somehow both alienating and extremely comforting. Something he is saying is something I feel, but I can’t annunciate it without writing back to him.

One Friday afternoon in October this year I sat on the roof of my house with two of my friends watching people pack up and leave for fall break. One of my friends was playing the guitar and my other friend and I were chatting softly.

“What were you writing today in class?” she asked me.

I looked down, embarrassed she’d caught me so obviously not taking notes on John Donne in our English seminar that morning. Still, I gracefully climbed through the open window and brought out Letters to Strangers. I opened to “Letter to a Mute” and handed the book to her, watching nervously as she read through the poem that I had scribbled out by memory on the pages of my notebook that morning.

When she looked up, she turned to me and said, “That’s like my life.”

We sat there quietly and I wondered if I’d spread the disease to her the way my AP Literature teacher had to me. – Gem McHaffey

Gem McHaffey is a sophomore English major at Wesleyan University. Her work has been published in publications such as Spry Literary Journal and Midriff Magazine and is the 2018 recipient of the Cole Prize for Creative Writing.

Learn more about Thomas James here.